All broadband radio service (BRS) and educational broadband service (EBS) licensees are required to make a showing to the Federal Communications Commission that they have provided a “service which is sound, favorable and substantially above the level of mediocre service which just might minimally warrant renewal” of their BRS or EBS license. To help provide limited clarity for this vague mandate, the FCC released a public notice on Friday to give guidance on what it expects licensees to submit and when. The notice made clear that the deadline for EBS licensees and BRS Basic Trading Area (BTA) licensees to file their notifications is Monday, May 16, 2011 and for BRS incumbent licensees that expire on May 1, 2011, the deadline is May 2, 2011, the same deadline as for the filing of their renewal application. The public notice comes as the FCC is accepting public comment on a proposal filed by the National EBS Association (NEBSA) and others – with the support of numerous licensees and commercial operators – requesting that the FCC grant a blanket extension of six months.

The main point for all licensees and operators: facilities need to be built and actual service needs to be provided to pass the substantial service test with flying colors.

Here is what you need to know:

First, until May 16, 2011, EBS licensees and BRS BTA licensees can electronically file "substantial service" showings via the Universal Licensing System (ULS). BRS "incumbent" licensees must file their "substantial service" showings as part of license renewal applications on or before May 2, 2011. "Substantial service" notifications are filed on Form 601 as "NT" filings with an appropriate exhibit (discussed below). Though the filing process has already begun, the FCC would not guarantee when it might begin to take action on individual "substantial service" showings. The FCC did say, however, that it doesn't plan to wait for all notifications to be filed before taking action. In cases where a "substantial service" showing is lacking, FCC staff said it will afford the licensee an opportunity to provide clarity or further information. In these cases, the FCC indicated that it would return the notification to the applicant and would provide the licensee with a deadline to submit additional information. The FCC may also informally contact a licensee or its counsel for follow-up, so having accurate contact information in ULS is a must.

Second, the FCC plans to "accept" many "substantial service" notifications only by providing notice in ULS – in other words, there will be no public notice of filing or of acceptance. In some cases -- presumably the more tricky ones or cases where the FCC concludes a licensee has failed to pass the "substantial service" test – the FCC will issue written decisions. FCC staff also confirmed to me that there is no right in the rules for parties to file petitions to deny against "substantial service" notifications or against requests for extension of time to comply. It is hoped that this will deter frivolous filings made only to obstruct or cause delay and mischief.

Third, the public notice also makes clear that the FCC will not review any "substantial service" showing filed by a licensee that has transitioned but has not filed its post-transition modification application to change to the "new" frequencies. In response to my suggestion, FCC staff also indicated that "acceptance" in ULS of compliant "substantial service" showings would be the only FCC action -- this would put investors on notice that they should not wait for a public notice announcing "acceptance."

Fourth, any licensee that does not file a "substantial service" showing (by the May 16 filing deadline) or an extension request (by May 1) will have its license automatically terminated. This statement presumes, of course, that the Commission does not grant the pending request for a six-month extension for EBS.

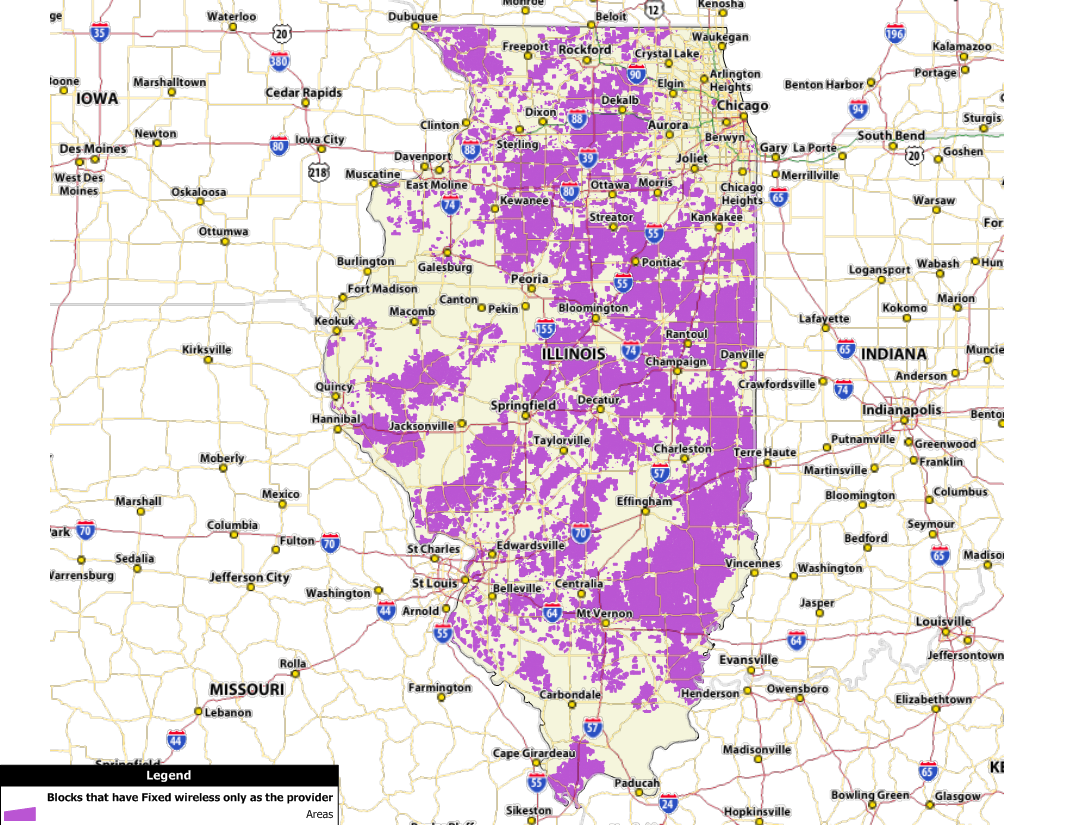

FCC staff offered some guidance on what it will be looking for in "substantial service" notifications. In all cases, the licensee must demonstrate "substantial service" within its geographic service area ("GSA") – service in white spaces or adjacent areas will not count. For BRS and EBS point-to-multipoint and mobile operations relying on the 30% coverage "safe harbor," licensees should include a map showing where they provide a "reasonably reliable" signal using generally acceptable engineering practices. Clearwire is developing a methodology for calculating coverage percentages, so perhaps all licensees can get behind a single method. Licensees are required to use the most recent official Census data. Licensees also need to indicate the type of service they are providing. For BRS and EBS licensees relying on the point-to-point "safe harbor" of six permanent links per million pops, the FCC will not require the submission of maps but will want a list of the endpoint coordinates and a description of the spectrum use. In addition, licensees relying on the rural service “safe harbor” (i.e., for mobile services, coverage to at least 75% of the geographic area of at least 30% of the rural areas within the service area and for fixed services, construction of at least one end of a permanent link in at least 30% of the rural areas within its licensed area) must provide in addition to the other information applicable to their type of service the area and population for counties that the licensee considers “rural” and must indicate which rural counties are receiving service.

For EBS, the FCC will be looking for a more detailed demonstration for licensees that are relying solely on their educational usage “safe harbor” and do not meet other "safe harbors” (including the 30% coverage, permanent links or the rural safe harbors). At a minimum, EBS licensees should submit a brief description of (1) the services they are providing in the GSA, and (2) how they are meeting the educational programming and minimum usage requirements. I note the use of the word “and” is in the Public Notice despite the fact that the version of the rule in the Code of Federal Regulations (p.330), in the associated Federal Register publication (p. 35190) and in the attachment to the FCC Order adopting the rule (p.165) uses the word “or.” This may be largely academic because the FCC has wide latitude to interpret its rules and it has repeatedly warned EBS licensees that actual service and use of 20 hours per channel per week is required. Merely transmitting signals is not enough.

There are some surprises relating to the amount of detail that is to be provided in the substantial service showing, based on the FCC's Public Notice:

- Licensees relying on the "permanent links" safe harbor must provide, in addition to the coordinates of each end of each link, the population within the geographic service area, an indication of the uses for the links and the bandwidth of the links;

- Licensees relying on the "30 percent coverage" safe harbor must indicate the signal level that they believe indicates coverage and the percentage of time such a signal is available within the service area; and

- Licensees relying on the "EBS" safe harbor must provide, in addition to specific descriptions of the service being provided, the names and addresses of any accredited institutions to which the licensee is providing service.

The FCC is sensitive to the workload (ours and theirs) and will not require detailed showings of things like programming schedules, though it will require addresses where service is being provided if it is not being provided to the licensee itself. Licensees that have channel-loaded or channel-shifted should mention this in their exhibits.

Finally, a few words about extensions. The FCC will look at extension requests on a case-by-case basis, and such requests should be filed at least 30 days before May 1. Though the FCC did not offer a lot of guidance, we expect that a licensee would need to demonstrate that financial difficulties or events beyond its control require additional time and that it is reasonable for the licensee to meet "substantial service" in the near future. Extensions also will be filed on Form 601 with the "EX" application code.

Given the lack of any objections in Comments filed last week and the FCC staff’s “receptiveness” to the needs of educators, prospects are excellent that the FCC will grant the blanket extension some time after March 1 when Reply Comments are due. My view is that the blanket extension will be granted this week by March 4th (this is the week of the national NEBSA conference) by circulation to the FCC Commissioners. After all, it would be unfair to leave licensees twisting in the wind not knowing if more time will be provided.

There is some concern that a government shutdown this week could throw a monkey wrench in the whole process. The reason is that ULS will automatically cancel the EBS license if a substantial service showing is not timely made, and of course if the government is shut down, so is the FCC – and ULS. While it seems unlikely that a government shutdown would extend beyond the applicable deadlines, no one wants to risk losing operating authority, so some licensees may rush to file their showing before Friday’s possible shutdown. If not, having lived through the last shutdown, I believe that there is little risk licenses will be lost during the FCC closure – if it even happens.

The main point for all licensees and operators: facilities need to be built and actual service needs to be provided to pass the substantial service test with flying colors.